Middle Colonies Native American Relations

Essay

Indian-brokered alliances more than Quaker pacifism anchored the "long peace" in the decades that followed Pennsylvania's founding in 1681. The Iroquois Covenant Chain and the Lenapes' treaties with William Penn (1644-1718) established the diplomatic parameters that made the long peace possible and immune Pennsylvania to avoid the kind of destructive frontier warfare that engulfed the Chesapeake and New England during Salary's Rebellion and King Philip'south State of war (1675-76). By the third decade of the eighteenth century, all the same, the fragile residuum betwixt Indians and colonists unraveled every bit Pennsylvania officials, with Iroquois permission, expropriated native lands in order to conform the westward migration of English, German, and Scots-Irish colonists. Few colonists appreciated in 1753 how their dispossession of Indian communities motivated the Lenape and other Indian groups to assail Pennsylvania'southward frontier towns during the Vii Years' State of war (1754-1763).

In the mid-1600s, upheavals among Indians in the Slap-up Lakes and Ohio Valley regions helped clear the way for the European settlement of the Delaware Valley. The Iroquois, equipped with Dutch (and after English language) firearms, struck out against the Huron and other native groups to secure fur trading routes and take captives to furnish their numbers, which had been decimated past European diseases. By the time Charles Ii (1630-85) granted Penn his colonial charter, Iroquois raids had largely depopulated the Susquehanna Valley of its native inhabitants.

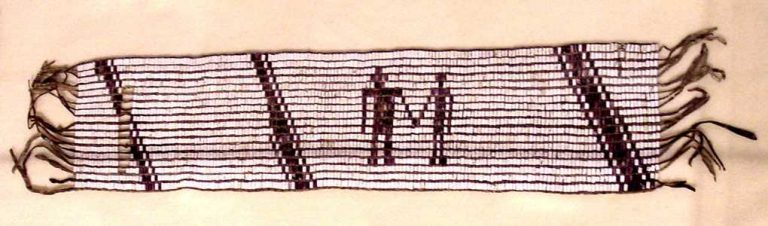

The Lenapes, or Delawares, who lived on both sides of the Delaware River, had been dealing with Dutch and Swedish colonists for decades and in 1675-77 sold lands in what became West New Jersey to English Quakers. Beginning in 1682, the Lenapes ceded lands on the w banking company of the Delaware to Penn in commutation for textile, guns, powder, alcohol, and other trade appurtenances. Lenape chiefs such every bit Tamanend (Tammany) did not "sell" land every bit much as grant shared usage rights in the hopes of establishing a human relationship with a potentially powerful European marry.

Common Benefits

With the Susquehanna Valley open for hunting beaver and other pelts that Europeans prized for Atlantic markets, the Lenapes were tending to negotiate with Penn, a man they called Miquon (meaning "feather," or quill pen, a Delaware pun on his last name). Penn, in return, promised he would deal with Indians honestly and fairly. These early treaties cemented Pennsylvania's reputation as a peaceable colony where beloved and friendship prevailed between Indians and colonists, as famously portrayed later by the paintings of Benjamin West (1738-1820) and Edward Hicks (1780-1849).

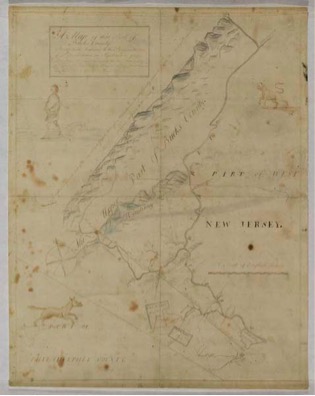

William Penn, the Quaker founder and proprietor, badly needed Indian partners. New York and Connecticut each claimed territory south of where Pennsylvania stock-still its northern border, while Maryland'southward Charles Calvert (1637-1715), Lord Baltimore, hotly disputed the location of Pennsylvania's southern boundary. One reading of Maryland's charter, in fact, placed that colony's upper border northward of Philadelphia. Penn used Indian titles to legitimate his country claims and ward off rivals. He also coveted Indian lands in the Susquehanna Valley, west of Philadelphia. By the early 1690s, Indians, fleeing warfare and colonization elsewhere, began settling the Susquehanna, including Lenape communities relocating to escape the growing colonial population in the Delaware Valley. They were joined by returning Susquehannocks (the original inhabitants of the region, now known as "Conestogas"), Shawnees, Mahicans, Senecas, Cayugas, Nanticokes, and Conoys, among others. These native settlers formed polyglot, multiethnic communities in Indian towns similar Conestoga, Pequea, and, a little subsequently, Shamokin.

Even before Penn consulted with Indian leaders in those communities, he sold colonists subscriptions to lands in the Susquehanna. Penn viewed the lower Susquehanna, with its access to the Chesapeake, every bit strategically vital to Pennsylvania'south commercial success. By attracting colonists there, he as well hoped to redirect the lucrative Indian fur trade away from Albany, New York.

Fortunately for Penn, Indians in the Susquehanna had good reasons to accommodate colonists. The Iroquois claimed the region by right of conquest (attributable to their mid-seventeenth-century raids), and through their Covenant Chain alliance with New York, they too claimed to speak on behalf of all Indian groups living there. Subsequently Governor Thomas Dongan (1634-1715) of New York sold Penn his merits to the Susquehanna for a meager £100, Shawnee, Conoy, and Conestoga leaders seized the opportunity to recognize Pennsylvania's potency in 1701. In doing so, they sought political legitimacy (at the expense of the Iroquois) as well equally a valuable trading partner. As he did near 2 decades earlier, Penn promised his Indian allies that his government would protect them from unruly colonists and dishonest traders.

Peace Preserved by "Become-betweens"

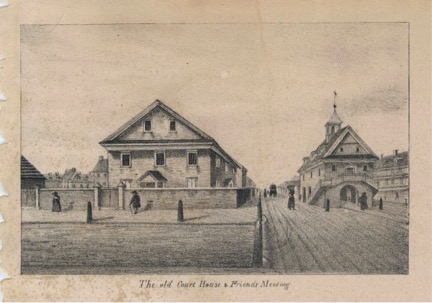

The 1701 treaty ensured Pennsylvania's "long peace" would continue, although uneasily. It was held together past diplomatic "go-betweens," Indian and colonial, who smoothed over the inevitable conflicts that arose in a borderland zone of multiple and overlapping native jurisdictions and where Pennsylvania held little authority. In one notable case, in 1722, the murder of an Indian named Sawantaeny (d. 1722) by an English trader, John Cartlidge (1684-1722), during a drunken ball touched off a diplomatic crisis that sent Pennsylvania officials to the Susquehanna Indian boondocks of Conestoga (and the governor to Albany because Sawantaeny was a Seneca Iroquois). The willingness of the Iroquois, provincial government, and Susquehanna Indians to overlook the murder and forgive Cartlidge (who eventually was freed after the Iroquois received restitution) demonstrated the value of maintaining good relations on the frontier, where political stability was necessary for peaceful coexistence and the continued profitability of the fur merchandise. It also demonstrated that the Pennsylvania government understood the importance of observing Indian diplomatic protocols, especially during a political crisis.

The provincial official who led Pennsylvania's investigation of Sawantaeny's murder, James Logan (1674-1751), had an interest in maintaining order in the Susquehanna. The son of Scottish Quaker converts, Logan came to Pennsylvania in 1699 to serve as Penn's provincial secretarial assistant. Shortly before leaving the colony in 1701, Penn entrusted Logan to wait after his proprietary interests and manage his estate at Pennsbury. Logan remained in Pennsylvania for the remainder of his life. During that fourth dimension, he became a major political figure, serving, among other positions, as provincial councilor, land commissioner, and Pennsylvania's master Indian diplomat. He ran a successful merchant concern in Philadelphia that supplied Indian customers using a cartel of traders who hauled his dry out appurtenances and rum into the Susquehanna on "Conestoga" wagons. By 1720, Logan had monopolized the fur trade and became i of the wealthiest colonists in Philadelphia.

Logan likewise engineered the "Walking Purchase," one of the most infamous chapters in the history of Native American-Pennsylvania relations. In 1737, Logan and Thomas Penn (1702-75), so acting as Pennsylvania'southward governor, claimed to possess a 1686 deed from the Lenape chief Mechkilikishi granting William Penn all the Indian lands that could be caused within a 24-hour interval-and-a-one-half's walk from Wrightstown in Bucks County. Although the deed was probably forged, the Iroquois sanctioned the "walk," which took identify in September with three of the colony'due south fastest runners roofing more than threescore miles. Logan used the "running walk," as the Lenape termed it, to claim over a thou square miles of Indian territory in the Delaware Forks (or in Lenape, Lechauwitank), where the Delaware and Lehigh Rivers converge (and where Allentown and Bethlehem are now located). Nether pressure from the Iroquois, the Lenape in the region, along with their leader, Nutimus, were forced to relocate to the Wyoming Valley (near present-mean solar day Wilkes-Barre) and Shamokin.

The Walking Buy and the colonization of the Susquehanna Valley left a bitter legacy in Pennsylvania-Native American relations. The Lenape chief Teedyuscung (c. 1700-63), who was among those displaced from the Delaware Forks, reemerged in the Wyoming Valley as a warrior who conducted periodic raids on Euroamerican settlements in eastern Pennsylvania during the Seven Years' War. In a strange twist, he took part in the Treaty of Easton in 1758 as an ally of the Quakers and helped to broker a peace between the Pennsylvania government and Ohio Valley Indians, primarily Lenapes and Shawnees who had been displaced earlier from the Susquehanna. Murdered in 1763 by arsonists who burned his motel nether mysterious circumstances (likely colonists from Connecticut's Susquehanna Company), Teedyuscung did not live to encounter many of his people forced to relocate again, under British regal and Iroquois pressure, west of the Appalachians. His life and decease, still, symbolized the entangled and intimate relations of Pennsylvanians and Native Americans through the beginning one-half of the eighteenth century.

Michael Goode is an Assistant Professor of Early on American History at Utah Valley Academy, Orem, Utah. (Writer information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Respectfully Remembering the Affable One (Subconscious City Philadelphia)

- Conestoga Indian Town [American Revolution} Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Lenape Nation Website

Middle Colonies Native American Relations,

Source: https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/native-american-pennsylvania-relations-1681-1753/

Posted by: webbageres.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Middle Colonies Native American Relations"

Post a Comment